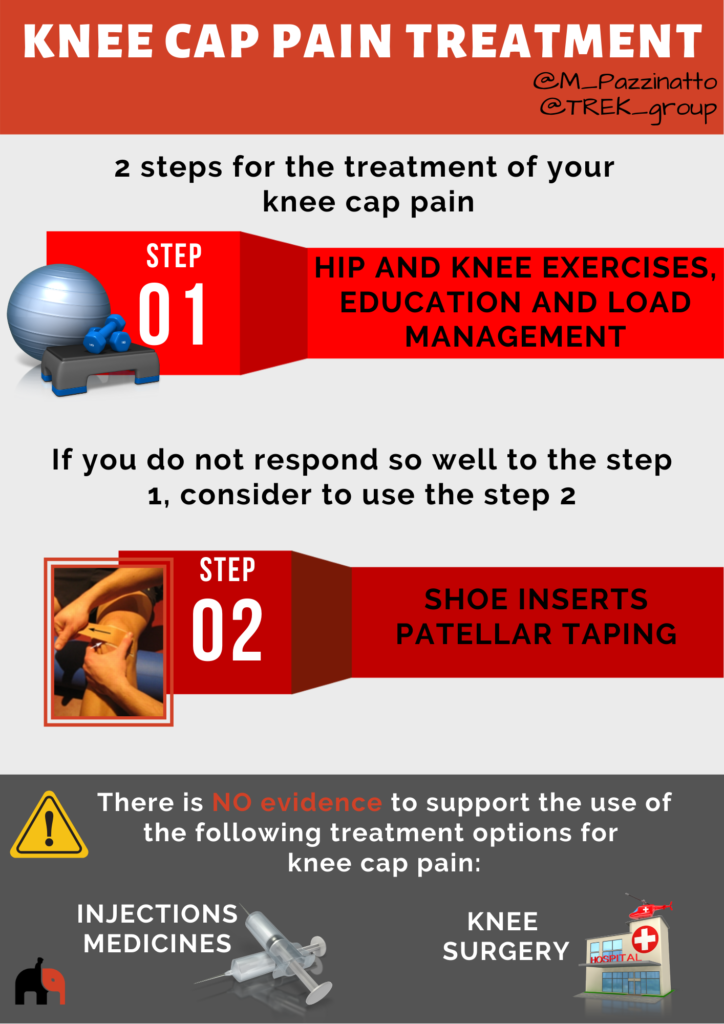

In this section, you can find what evidence-based treatments are most likely to help you.

Listen to world renowned physiotherapist and expert in managing knee cap pain, Professor Kay Crossley (La Trobe Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre) discuss surgery, exercise and other treatments for knee cap pain:

In this section, you can learn more about the treatment options you have.

There are a plenty of exercises you could do to improve your knee cap pain, but, some are better than others.

See the video below to choose the more effective exercises.

In the bookcase below you will find a simple and a complete exercise guidance to help you progress your exercises.

Why is it important to complete exercises targeting my hip muscles?

People with knee cap pain generally have weak and poorly functioning hip muscles. It is thought that this weakness and poor function may not be the reason as to why you develop pain in the first place. Instead, your hip muscles may become weak because you have changed the way you move, or move less to avoid pain.

Weak and poorly functioning hip muscles are thought to put more stress onto your knee cap during activities like running, walking on stairs and squatting. This is because the muscles can no longer control your thigh well enough, allowing it to roll under the knee cap.

A good way to understand this, is to think of your knee cap as the train, and your thigh as the tracks. If the train (knee cap) moves or tries to derail off the tracks (thigh), this can be because your thigh muscles don’t control the train well enough. However, when the hip is not controlled well enough, the tracks (or thigh) may move underneath the train, having the same derailing effect.

A number of good research trials report that hip targeted exercises are effective in reducing knee cap pain. In the longer term, combining both thigh and hip muscle targeted exercise is the most effective approach to reduce pain.

Supporting articles

Barton 2013. Gluteal muscle activity and patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review.

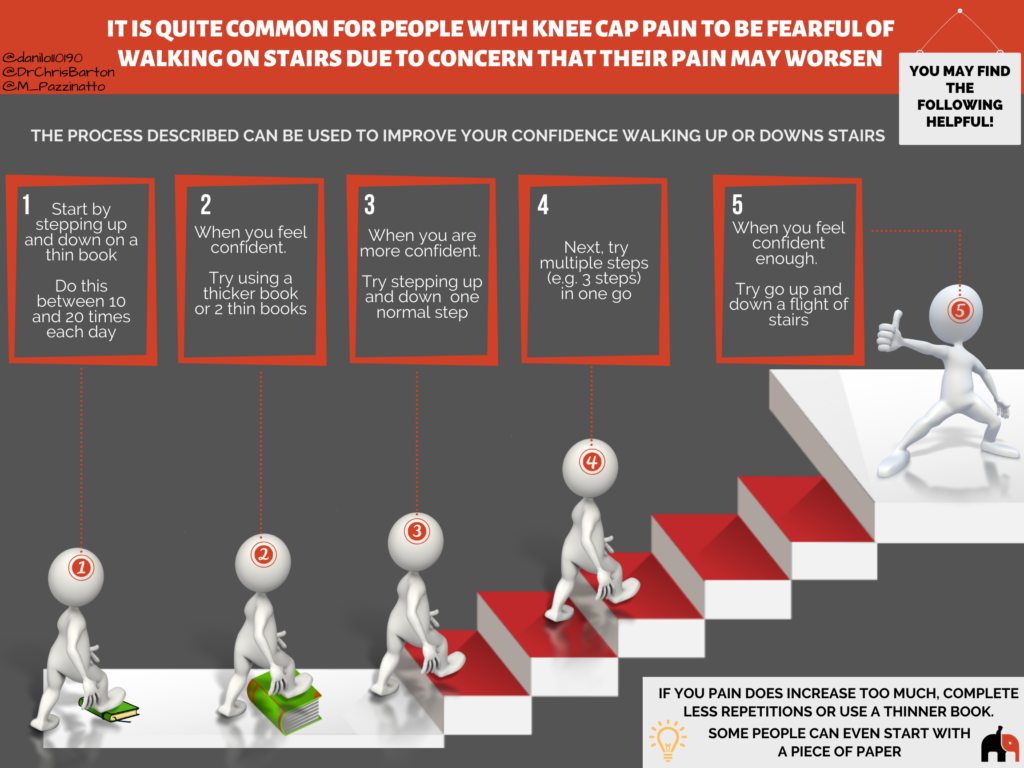

Fear of pain and movement may exist in patients with knee cap pain. However, the most recommended intervention for knee cap pain is exercise, passive treatments are not likely to help.

Despite being quite common for patients with knee cap pain to be fearful of some movements (e.g. running, jumping and walking on stairs). Some studies report that reductions in fear of movement are related with reductions in the level of knee pain. Therefore, it is highly recommended for patients to keep doing all daily activities alongside the exercise program.

If you are not so confident to walking on stairs at the moment, you may find the following infographic helpful.

Supporting articles

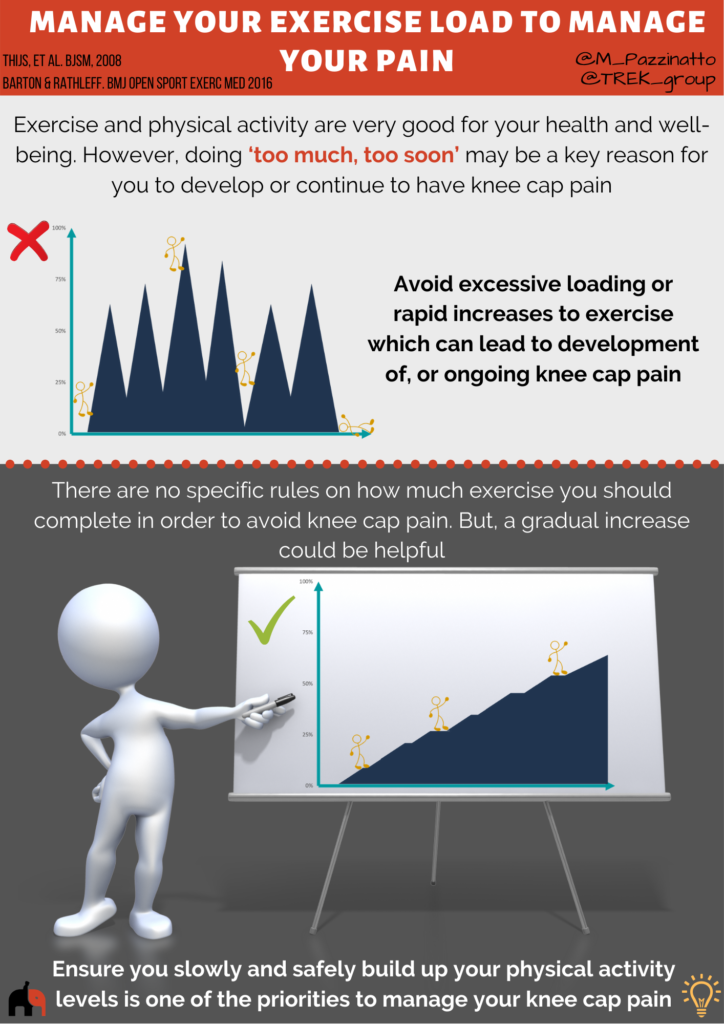

Exercise and physical activity is very good for your health and well-being. However, doing ‘too much, too soon’ may be a key reason you develop or continue to have knee cap pain?

If you are not sensible with how much exercise you do, other normally effective treatments may not actually end up helping you manage your pain. That’s why managing load is very important.

Take a look at the short video below to get some tips on how you can manage your exercise and physical activity loads (it’s less than two mins)!

Why do I need to be sensible with how much exercise I do?

The exact reason why people develop knee cap pain is unclear. However, experts around the world tend agree that doing ‘too much, too soon’ in relation to exercise may be a key reason.

There seems to be a spike in the number of people with knee cap pain following rapid increases to how much exercise you do – e.g. basic military training or ‘start to run’ programs (e.g. couch to 5KTM).

In ‘start to run’ programs it can be as high as 17%.

There are no specific rules on how much exercise you should complete in order to avoid developing knee cap pain. It is also not clear exactly how quickly to increase exercise when returning to sports and other activities if you are recovering from knee cap pain.

The most sensible option is to monitor your pain levels during and after exercise. Experts frequently recommend that if you have a large increase in pain, or pain stays increased for more than 24 hours after exercise, you may be doing ‘too much, too soon’.

Further guidance on how much exercise you should do and how quickly to increase it can be provided by your physiotherapist.

Supporting articles

Barton 2016. ‘Managing My Patellofemoral Pain’: the creation of an education leaflet for patients.

Knee cap pain is common in runners. But, the good news is that through simple tips you can improve your knee cap pain. We recommend that if you have knee cap pain during running, you should:

- Keep your pain at no more than 2/10 during running. For reference, 0 = no pain; and 10 = the worst pain you could imagine.

- Knee pain needs to return to pre-training level within 60 minutes post-training, without increases in the following morning.

Here are 5 tips to help you achieve less pain during and after running (see the video, infographic and the text below):

1. Increase training frequency to decrease each session’s duration (for example, instead of running 5km, 3 times in a week, run 3km, 5 times in a week).

2. Decrease your running speed by approximately 10-20%. For example, if you normally run 5 minutes per km, try running at 6 minutes per km.

3. Try using a run-walk program where you have walking breaks. For example, run for 4 minutes, walk for 1 minute.

4. Avoid downhill and stairs running, and gradually reintroduce once pain has settled to an acceptable level (no more than 2/10).

5. Try increasing the number of steps you take per minute, without running faster. It is often achievable to increase by between 5 and 10%, and this frequently leads to less load on your knees. This can be done by thinking about taking shorter faster steps, using a metronome, or running with music at a set tempo (beats per minute) similar to how many steps per minute you aim to take. According to experts, this is likely to be most effective in people who take 170 or less steps per minute.

As your pain reduces, you may gradually reintroduce your normal running behaviour, including returning to longer runs, increasing speed, removing walking breaks and reintroducing hills and stairs. Try to only change one thing at a time, and ensure as you do this, your pain remains no more than 2/10.

For further information see the links:

Why might shoe inserts help?

Research suggests that shoe inserts will significantly help reduce pain in anywhere between 25 and 50% of people with knee cap pain over the first 6-12 weeks of treatment. They may also help in the longer term too.

Traditionally, shoe inserts have been provided to people because they have flat (pronated) feet. However, there is a lot of debate about whether this is the right approach. In people with knee cap pain, having flatter feet does not predict strongly whether or not shoe inserts will help. Equally, shoe inserts can help people who are not considered to have flat feet.

A couple of studies have reported that people with flexible feet measured using a specific device are more likely benefit from shoe inserts if they have knee cap pain. This is something you could discuss and assess with the assistance of your physiotherapist or podiatrist.

One of the simplest ways to work out if shoe inserts will help is to try them during an activity that normally causes pain. If the inserts immediately reduce your pain, then they are likely to help. If they do not immediately reduce pain, they are unlikely to help you. It is that simple!

In one study, this test was the strongest predictor of success with shoe inserts given to people with knee cap pain. In the same study, the amount of foot movement (pronation) occurring during walking also predicted success, but not as well.

Aren’t shoe inserts expensive?

If shoe inserts are customised specifically for you by a podiatrist, they can be quite expensive. However, research tells us that this is not necessary for most people with knee cap pain.

Less expensive prefabricated shoe inserts (usually less than $100) can be used to treat knee cap pain. If you complete your rehabilitation exercises given to you by a physiotherapist and get stronger, shoe inserts may only be needed for a short time.

Some physiotherapists have the knowledge and skills to provide you shoe inserts and you should discuss this with the physiotherapist treating you. If not, they can refer you to see a podiatrist to help.

Supporting articles

Barton 2011. Clinical predictors of foot orthoses efficacy in individuals with patellofemoral pain.

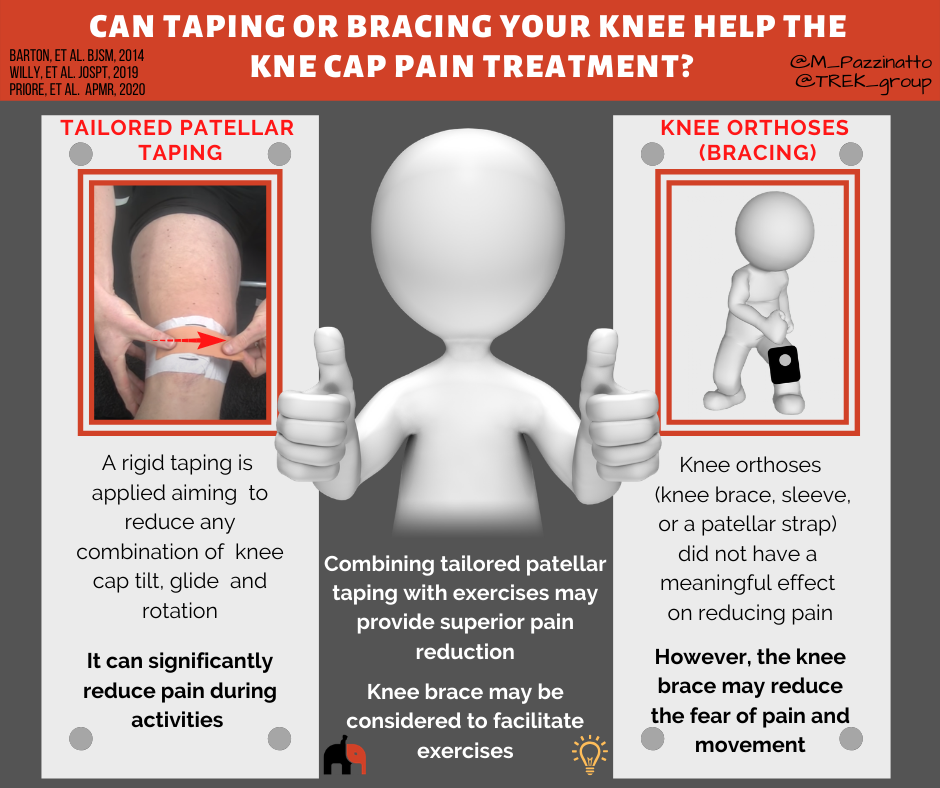

Patellar taping

The most effective way to tape you knee can be different for each person, and research shows that tailoring it to your needs may optimise how much pain reduction you get. You may wish to discuss this with your physiotherapist who can assess your knee and find the most effective way for you.

Based on the best evidence available, the following taping technique may be worth trying:

Importantly, taping techniques are most likely to reduce pain and improve physical function during accompanying exercise program.

Knee Orthoses

Studies revealed that knee orthoses (knee brace, sleeve, or a patellar strap) is not able to reduce pain more than exercise. However, the knee brace may reduce the fear of pain and movement. The use of a knee brace may work as a strategy to improve exercise compliance by reducing fear or even as a mediator to reduce pain and improve physical function.

Additionally, using a medially directed realignment brace while exercising leads to better outcomes in patients with knee cap pain than exercise alone after 6 and 12 weeks of treatment.

Supporting articles

In this section, you can find more information about adjunct treatments for knee cap pain

Blood Flow Restriction

Blood flow restriction training involves exercise whilst using a pneumatic cuff to restrict blood flow, similar to a blood pressure cuff. The decreased oxygen to the muscle, in combination with reduced ability to get rid of waste products from the exercise (e.g. lactic acid), causes the muscle to work a lot harder than without occlusion.

Blood flow restriction may in theory be very beneficial in people with musculoskeletal pain who need to get stronger to improve the management of their condition but pain stops completing an adequate gym program.

An 8-week of blood flow restriction training may provide a low-load thigh muscles strengthening and reduction in pain with daily living activities.

Passive treatment options (with machines)

There is a variety of therapeutic modalities of passive treatment:

Cryotherapy (ice therapy or cold therapy) is a technique where the body or one area of the body (e.g. knee) is exposed to extremely cold temperatures for several minutes. It can be administered in a number of ways, including through ice packs, ice massage, ice baths.

Laser therapy and therapeutic ultrasound are  popular modalities commonly used in physiotherapy clinics. Laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) therapy is the application of red and infrared light over the injuries. And the therapeutic ultrasound consists in a small handheld probe placed on the problem area (e.g. knee) combined with gel or cream, which may be medicated or not. The probe vibrates, sending waves through the skin and into the body.

popular modalities commonly used in physiotherapy clinics. Laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) therapy is the application of red and infrared light over the injuries. And the therapeutic ultrasound consists in a small handheld probe placed on the problem area (e.g. knee) combined with gel or cream, which may be medicated or not. The probe vibrates, sending waves through the skin and into the body.

Electrical stimulation also is a very popular modality used in physiotherapy clinics. Electrical stimulation is the use of electrical impulses to make the muscles contract or to provide pain relief. The electrodes attached to the skin deliver impulses that make the muscles contract.

Despite all these modalities are commonly used in physiotherapy clinics, they are not recommended for the treatment of people with knee cap pain. Any of these modalities add benefit when combined with exercises. As exercise therapy is the consistent component in combined intervention studies, these modalities should not reduce the time available to provide appropriate exercise therapy in patients with knee cap pain.

Manual Therapy

Although manual therapy, including lumbar, knee, or knee cap manipulation/mobilization, has been used in combined interventions, its use may not improve outcomes, particularly when used in isolation, and thus is not recommended.

As exercise therapy is the consistent component in combined intervention studies, manual therapy should not reduce the time available to provide appropriate exercise therapy in patients with knee cap pain.

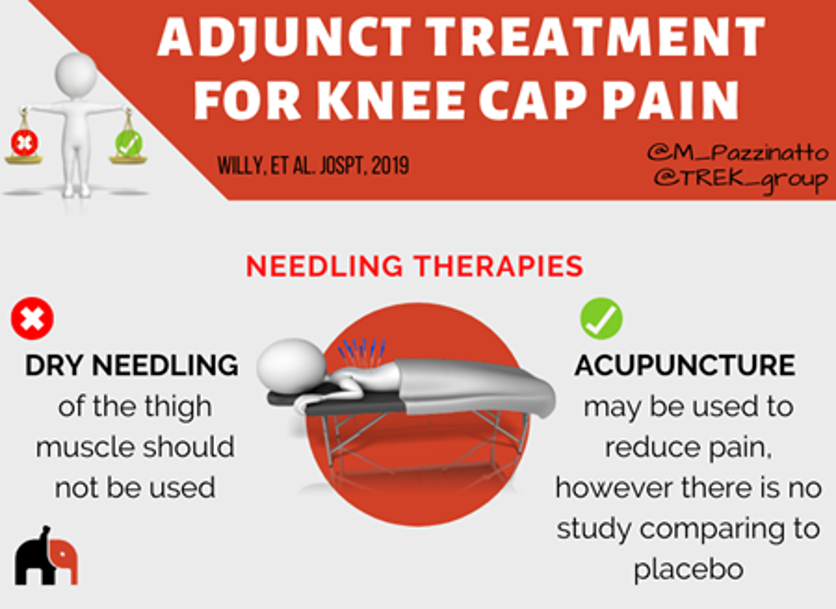

Needling Therapies

The two common forms of needling used in practice are:

Acupuncture (Eastern medicine) and Dry needling (Western medicine).

Acupuncture may be used to reduce pain in people with knee cap pain. However, caution should be exercised with this recommendation, as the superiority of acupuncture over placebo or sham treatments is unknown.

Dry needling of the thigh muscle is not better than placebo and it does not add improvements in pain or physical function when combined with knee exercises. Thus, dry needling is not recommended for the treatment of people with knee cap pain.

Supporting articles

In this section you will find information about medicines for knee cap pain.

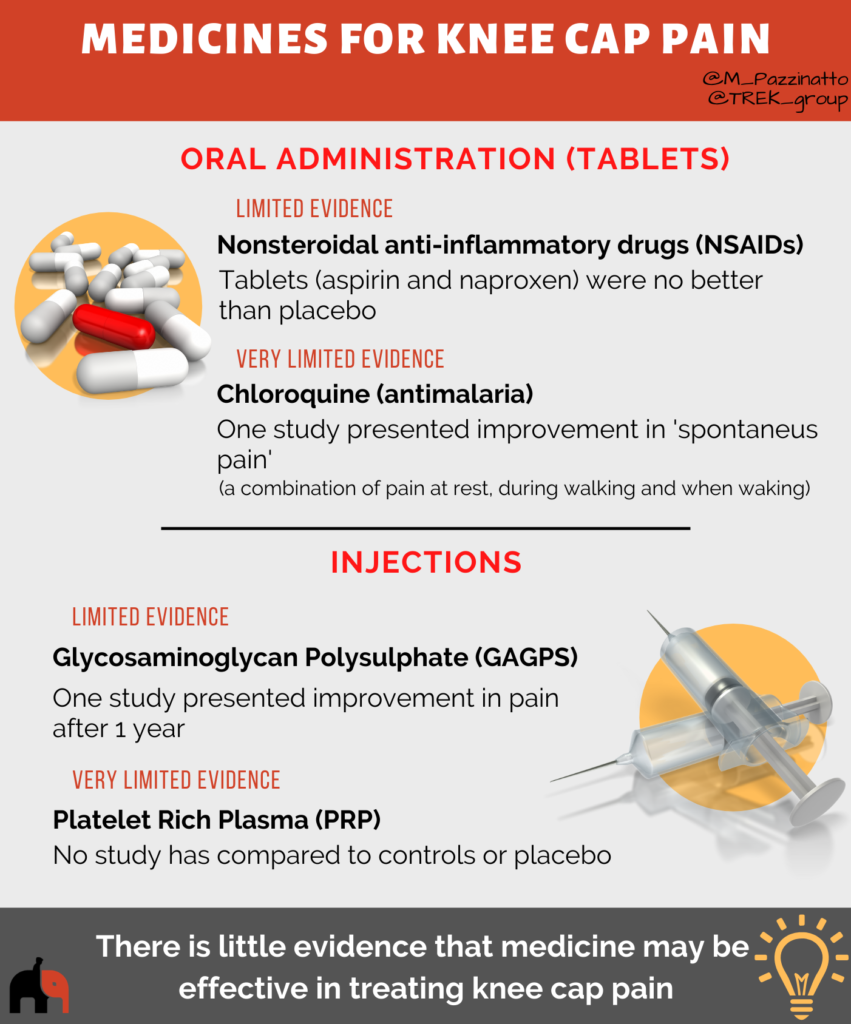

Medicines are generally prescribed to people with knee cap pain on the premise that they address underlying inflammation or structural abnormalities that cause the pain. However, as we see in previous sections of this website, pain and structure are not strongly correlated, and pain is complex and subjective. This may explain why some medicines offer no benefit over placebo.

The lack of reliable studies limits the ability to offer robust recommendations relate to medicine as a treatment option for people with knee cap pain.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are the most prescribed medications for persistent pain conditions. Most people are familiar with over-the-counter, nonprescription NSAIDs, such as aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen. However, NSAIDs are no better than placebo for reducing pain in people with knee cap pain.

Chloroquine (anti-malaria)

Chloroquine belongs to a group of medicines known as antimalarials. Only one study (1980) has investigate its effect in people with knee cap pain. Despite this study has presented improvement in ‘spontaneous pain’, caution should be exercised with this recommendation, as the superiority of chloroquine over other treatment options is unknown.

Glycosaminoglycan Polysulphate (GAGPS)

Glycosaminoglycan is a major component of joint cartilage and joint fluid. GAGPS is a substance that possibly decreases the degradative reactions that cause damage to cartilage. However, caution should be exercised with this recommendation, as the superiority of GAGPS over placebo or sham treatments is unknown.

Platelet-rich-plasma (PRP)

Platelet-rich-plasma (PRP) is the cellular component of the plasma with a higher percentage of platelets compared to total blood. Since it contains a number of growth factors, PRP injections in sports injury treatments became common today. However, there is no good evidence that PRP could be beneficial for people with knee cap pain.

Supporting articles

Fulkerson 1986. Comparison of diflunisal and naproxen for relief of anterior knee pain.

Matoso 1980. Essai clinique contôlé de la chloroquine dans la chondromalacie rotulienne.

Raatikainen 1990. Effect of glycosaminoglycan polysulfate on chondromalacia patellae.

See the video below to know more about this subject