In this section, you can learn more about knee cap pain by scrolling down the page.

You can also click on the links to the left to quickly access answers to common questions about your knee cap pain.

If you are a runner, we have a specific section for you here.

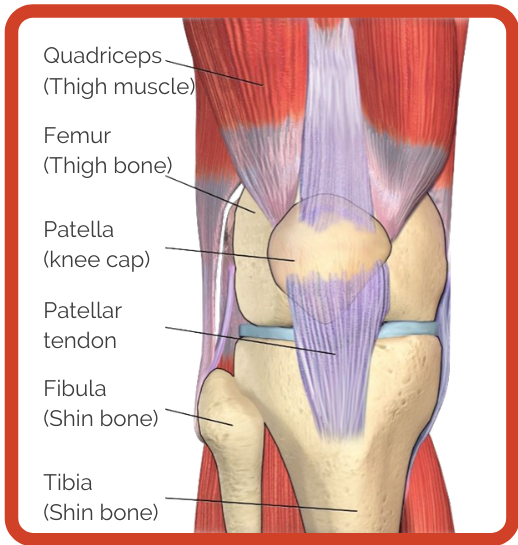

The knee is one of the largest and most complex joints in the body. The knee joins the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia). The smaller bone that runs alongside the tibia (fibula) and the kneecap (patella) are the other bones that make the knee joint.

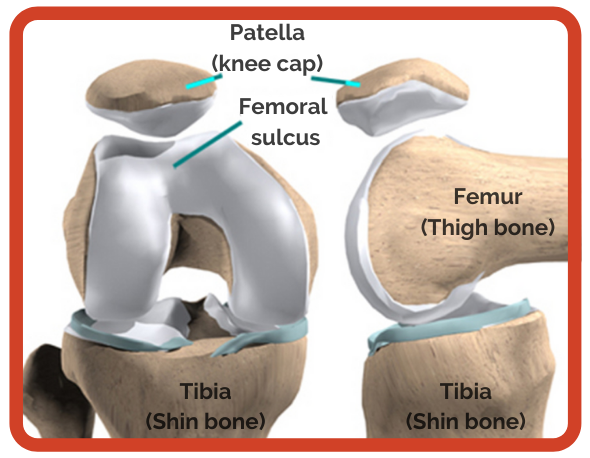

The patellofemoral joint consists, specifically, of the posterior surface of the patella (knee cap) and the surface of the femur (thigh bone). The patella (knee cap) is shaped like an upside-down triangle. On average, the patella (knee cap) is approximately 4 – 4.5 cm of length, 5 – 5.5 cm of width and 2 – 2.5 cm thick. The distal femur forms into an inverted U-shaped (femoral sulcus). During knee movement (bending and straightening), the patella (knee cap) glides over the femur (thigh bone).

Supporting articles

Loudon 2016. Biomechanics and pathomechanics of the patellofemoral joint.

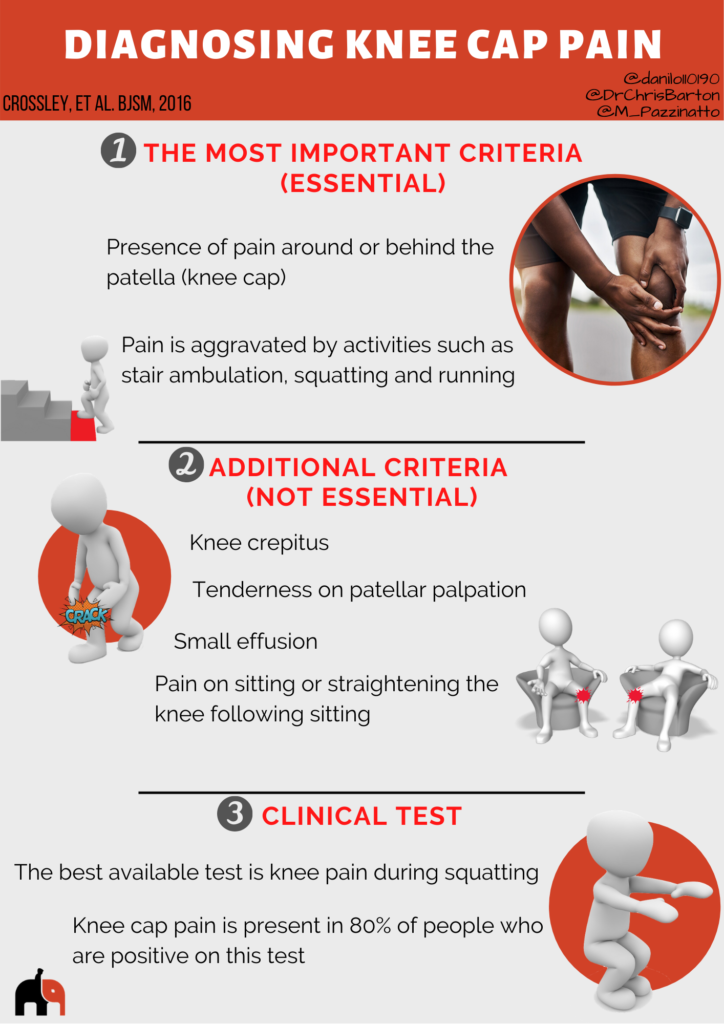

Diagnosis of your knee cap pain will most likely be termed patellofemoral pain, and should be provided by a suitably qualified health professional. Other common terms include chondromalacia patellae and runners knee.

This infographic does not replace consultation with a physiotherapist or doctor, but it might help you to understand if you have knee cap pain (patellofemoral pain).

Imaging (Scans)

Some people believe that changes in structure (e.g. cartilage) of the knee joint is the cause of knee cap pain. However, research suggests no difference between people with knee cap pain and people without pain on MRI and X-ray. Therefore, imaging is not likely to help with knee cap pain diagnosis, or in determining appropriate treatments.

Supporting articles

The factors that cause your knee to hurt are complex, and despite a lot of research are currently not completely clear. However, the infographic below helps to explain the most likely reasons.

Supporting articles

Dye 2005. The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: a tissue homeostasis perspective.

Maclachlan 2017. The psychological features of patellofemoral pain: a systematic review.

Knee cap pain is one of the most common knee conditions among adolescents, affecting up to 7% of this population. In adults, knee cap pain affects 17% of runners, and 23% of the general population.

Knee cap pain is two times more likely to affect women than men.

Supporting articles

Smith 2018. Incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Boling 2010. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Taunton 2002. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries.

Although knee cap pain has traditionally been viewed as self-limiting, it is common for pain to continue in the longer term, but research related to the number of people with ongoing pain is inconsistent.

Although knee cap pain has traditionally been viewed as self-limiting, it is common for pain to continue in the longer term, but research related to the number of people with ongoing pain is inconsistent.

Tailored physiotherapy involving exercise rehabilitation has been reported to significantly reduce pain in 60% of patients after 1-year. Longer term outcomes on the other hand have been shown to be a little more varied. One study has reported that if left untreated up to 90% of people with knee cap pain still report symptoms 18 years after their diagnosis.

Another study found that 57% of people were not happy with their outcomes between 5 and 8 years after receiving treatment for knee cap pain. It was also found that people with worse and longer duration of symptoms before starting treatment were more likely to not be happy with their outcomes.”

Regardless of the inconsistent research findings on how long pain might last, knee cap pain treatments including exercise, foot orthotics and taping can be effective in short-term. Thus, key factors for having a better long-term outcome are likely to be using these effective treatments.

Supporting articles

Collins 2013. Prognostic factors for patellofemoral pain: a multicentre observational analysis.

Sandow 1985. The natural history of anterior knee pain in adolescents.

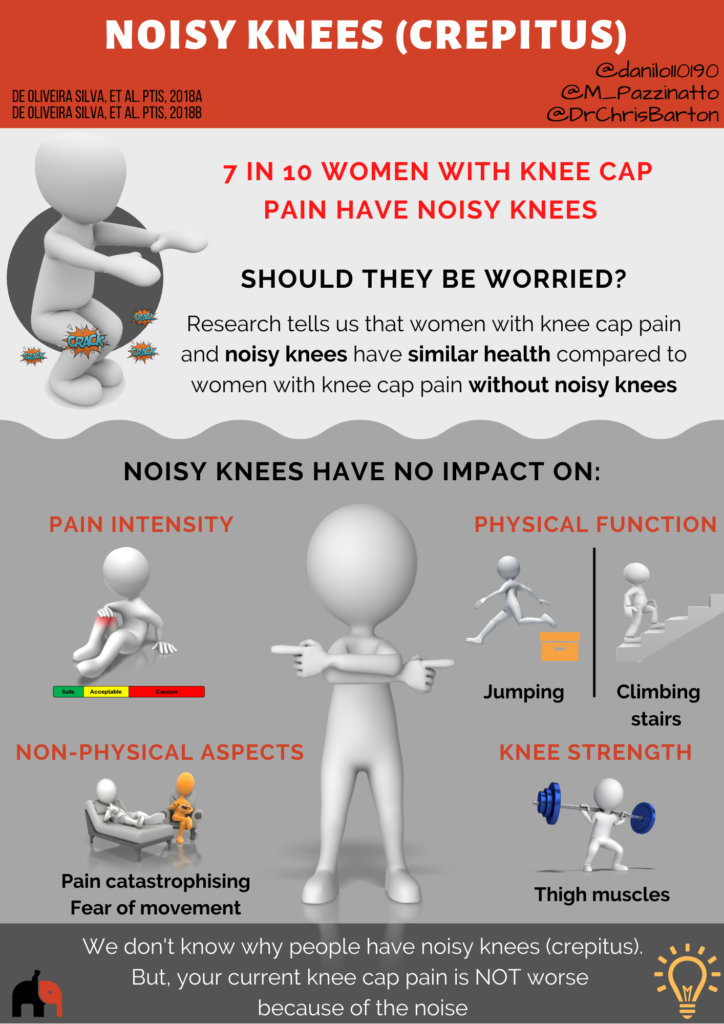

Noisy knee or knee crepitus is a common complaint/concern of people with knee cap pain. We don’t know what causes the noise on the knees. But, recent data show that people with knee cap pain who have noisy knees have similar levels of pain, function, fear of movement and knee strength compared to those who don’t have noisy knees. In other words, if you have knee cap pain and a noisy knee, it doesn’t mean your condition is worse than those who have knee cap pain and no noisy knee.

Additionally, a previous study investigated 250 asymptomatic knees (knees with no pain) and found that 99% of people had knee crepitus.

Supporting articles

Pain can often cause someone to become fearful of exercise.

However, complete rest is not helpful and it is common for you to have knee cap pain at the beginning of your exercise programs designed to help your knee pain.

Having some pain with exercise and rehabilitation is ok and not dangerous. Here we have 5 tips for you monitoring your knee cap pain during exercises.